One of the many times I fell in love with Sam revolved around him being head chef for a 22-person seder hosted in my 800 sq ft apartment, attended by 2 Jews, a hindu, a Morman-Pagan intermarried family, some agnostics and buddhists, lapsed Christians, and a whole mess of other folks whose religious predilections are second to their desire for food, friends, and family. We’ve hosted first-time Thanksgiving dinner for an ex-Jehova’s Witness and a vegetarian Easter brunch on a Passover Seder plate. Christmas usually involves socializing with the Mulveys, a windfall trip to Vegas (complete with a Christmas Eve Penn-&-Teller-show-cum-Star-Trek-Experience), or a ritual viewing of Santa Clause Conquers the Martians (MST3K version, of course) with take-out Chinese food. I’ll polish my oil lamp and light wicks for 8 days during Hannukah.

One of the many times I fell in love with Sam revolved around him being head chef for a 22-person seder hosted in my 800 sq ft apartment, attended by 2 Jews, a hindu, a Morman-Pagan intermarried family, some agnostics and buddhists, lapsed Christians, and a whole mess of other folks whose religious predilections are second to their desire for food, friends, and family. We’ve hosted first-time Thanksgiving dinner for an ex-Jehova’s Witness and a vegetarian Easter brunch on a Passover Seder plate. Christmas usually involves socializing with the Mulveys, a windfall trip to Vegas (complete with a Christmas Eve Penn-&-Teller-show-cum-Star-Trek-Experience), or a ritual viewing of Santa Clause Conquers the Martians (MST3K version, of course) with take-out Chinese food. I’ll polish my oil lamp and light wicks for 8 days during Hannukah.

These holidays, observed by the vast majority of people in some religious sense, are easy to adapt for atheists thanks to a combination of commercialization, fun objects, seasonal rhythmic association, distinctive food, and a heavy emphasis on family unity and goodwill–very much human, and humanistic, qualities. The Jewish Days of Awe (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur) are not.

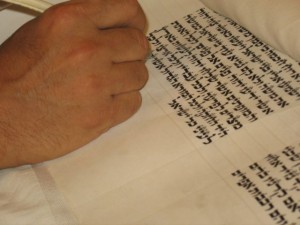

Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New year, is about the Jewish people’s relationship with their God and each individual Jewish person’s relationship God. It sets in motion ten days in which to repent one’s sins and seek forgiveness from those around you. The imagery is not one of rebirth, nor of light, nor of family unity; it is centered around the ever ominous Book of Life, the alarming blast of the ram’s horn, and the fevered chanting of a congregation. You’d better work your tail off to get your name inscribed in there before the sun sets on Yom Kippur, OR ELSE! (DUN Dun duuuun…)

Weirdly, as a practicing Jewish child and young adult, I always liked these holidays. I used to feel lucky that I didn’t have to confess every week like the Catholics! I felt at ease knowing that once a year I’d get to–have to–admit all I’d done wrong, that others would be doing the same thing, that we’d all be there to support each other, to take the fall for each other, and to mutually forgive each other.

Weirdly, as a practicing Jewish child and young adult, I always liked these holidays. I used to feel lucky that I didn’t have to confess every week like the Catholics! I felt at ease knowing that once a year I’d get to–have to–admit all I’d done wrong, that others would be doing the same thing, that we’d all be there to support each other, to take the fall for each other, and to mutually forgive each other.

Even as a regularly practicing Jew I had very little prayer-based relationship with any god; prayer was a purely human thing, one voice reaching another, bouncing around the sanctuary room. I never felt I was authentically connecting with anything during a solitary petitionary prayer—what am I, a six-year old Becky talking to her stuffed animals?–and I reasoned that Judaism understood this so well that it was the reason a prayer quorum was established for “real” worship. We weren’t praying to God; we were praying to each other and for each other. I relished hearing the usual liturgy set suddenly to plaintive, pleading tunes and triumphant endings. But why then, if we were all so excruciatingly regretful for our transgressions, would we be doing it all again next year? Did that not resign us to avoid carefully checking our behavior for its effects on the world around us and those we love?

For me at least, it did. That I would offend others was a given, and because it was a given, it was nothing that could be helped. I am now able and willing to critically examine the complex aspects of character that my involvement with Judaism perpetuated within me. Therefore, this Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I will create my own shofar blast. It will not serve as a rallying call for Jews to gather up yet again, make their “sorry” rounds, and grant de facto forgiveness. It will be a cry to cease treating interpersonal transgression as something which cannot be helped. And for having held steadfast to that practice for so long, I am sorry and ask your forgiveness.